Raja Mahamet

Extract from an article written in the Guardian in

2004.

Global villagers

Ian Jack on the virtues of curiosity

…….:-

The next year we moved to the village in Scotland where, so many years later,

the boys in the field saw a brown woman and told her to get back to the trees. The term "Scottish village"

has many connotations, almost all of them homely and almost all of them wrong. My village had been

thoroughly mixed up by the conflicts of the 20th century. Nearby, there was a naval dockyard and an

airbase or two, while the village itself held a small army barracks and a Royal Navy signal station.

Many of the children I knew were raised - a puzzle to me then - by their grandparents.

Here in the flat across the street from us lived my second black, or at least non-white, man: "The Raja".

What did we know of him? That he was brown and robust-looking and cheery; that for a living he caught

and cast off the ropes at the pier where the ferryboats came and went; that he lived with his daughter,

Maggie (our popular postwoman), and his Cornish son-in-law Norman, and his grand-daughter, May, who played in the street with us.

Eventually we also knew that he was from Malaya and had lived first in the village on the seashore in the "Nestlé Milk Huts",

so-called because their roofs were made of old enamel adverts for that brand of chocolate.

The Raja was a very friendly man, especially towards ferry-boat passengers who in the summer included

foreign tourists (it was said that he'd been round the world twice and could speak five languages),

and it was thanks to his gifts in this department that our little street witnessed the most exciting

event in its history. The Raja had encountered Malay's police pipe band on the ferryboat - it was around

the time of the Edinburgh Tattoo - and arranged that the entire outfit, drummers and pipers and pipe-major

and cooks, came to his very small council flat for lunch. I can still remember the big shining pans of rice,

and uniformed bandsmen balancing plates of curry and trying to find somewhere to sit in the front garden.

This week, thinking of Phillips's "passive apartheid", I rang May (who still lives in the same house) to ask about

her grandfather and what it was like to grow up not-quite-white in a Scottish village 50 years ago. She spelt out

his real name for me, Raja Mahamet, and said that he had come to England, perhaps to study medicine, but there

married a girl from Norwich, which caused his family to disinherit him. Then he began to look for work. He'd

sometimes spoken of a day or two he spent on the Jarrow march.

She remembered his precepts: how courtesy was vital at all times and how she must forgive and forget insults

because they came out of ignorance. Insults such as? "I did get upset at times at school when people said:

'You're a Chinkie!' or 'Your grandpa's black!'"

I grew up in the same street as she and had either never known of these insults or had forgotten I'd heard

them. Perhaps this is what Phillips means by "passive apartheid" - too little, rather than too much,

curiosity about the others in your midst, so that their individual humanity never emerges and they

remain strangers known by their colour. What is harder to believe is that it's worse now than it was,

or threatening to become so.

The Ferry News

Issue 71 June 2012

www.ferrynews.org.uk

Village Characters

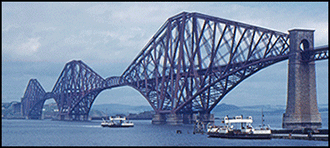

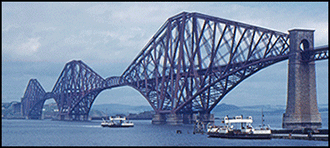

Another well remembered character was Raja Mahamet who was Pierman for the 'Queensferry Passage' at the

north side for many years. He was also an accomplished violin player. The children of the village especially

loved when he flew his home made kites at Queen Margaret's playing fields and he usually helped them to make

their own kites to fly in the Gala competition. Rajah's daughter, Maggie, was a post lady for the village

for 28 years and his grand-daughter May has been the Brownie leader in the village for 28 years, which shows

dedication.